7 Calibration

This page is a work in progress and minor changes will be made over time.

Calibration measures evaluate the ‘average’ quality of survival distribution predictions. In general there is a trade-off between discrimination and calibration. A model that makes perfect individual predictions (good discrimination) might be overfit to the data and make poor predictions on new, unseen data. Whereas a model that makes perfect population predictions (good calibration) might not be able to separate between individual observations. The literature around survival analysis calibration measures is scarce (Rahman et al. 2017), potentially due to the complexity of even defining calibration in a survival context (Van Houwelingen 2000). Though this meaning does become clearer as specific metrics are introduced. As with other measure classes, only measures that can generalize beyond Cox PH models are included here but note that several calibration measures for re-calibrating PH models have been discussed in the literature (Demler, Paynter, and Cook 2015; Van Houwelingen 2000).

Calibration measures can be grouped (Andres et al. 2018) into those that evaluate distributions at a single time-point, ‘1-Calibration’ or ‘Point Calibration’ measures, and those that evaluate distributions at all time-points ‘distributional-calibration’ or ‘probabilistic calibration’ measures. A point-calibration measure will evaluate a function of the predicted distribution at a single time-point whereas a probabilistic measure evaluates the distribution over a range of time-points; in both cases the evaluated quantity is compared to the observed outcome, \((t, \delta)\).

7.1 Point Calibration

Point calibration measures can be further divided into metrics that evaluate calibration at a single time-point (by reduction) and measures that evaluate an entire distribution by only considering the event time. The difference may sound subtle but it affects conclusions that can be drawn. In the first case, a calibration measure can only draw conclusions at that one time-point, whereas the second case can draw conclusions about the calibration of the entire distribution. This is the same caveat as using prediction error curves for scoring rules (Section 8.3).

7.1.1 Calibration by Reduction

Point calibration measures are implicitly reduction methods as they use classification methods to evaluate a full distribution based on a single point only (?sec-car). For example, given a predicted survival function \(\hat{S}\), one could calculate the survival function at a single time point, \(\hat{S}{\tau}\) and then use probabilistic classification calibration measures. Using this approach one may employ common calibration methods such as the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (Hosmer and Lemeshow 1980). Measuring calibration in this way can have significant drawbacks as a model may be well-calibrated at one time-point but poorly calibrated at all others (Haider et al. 2020). To mitigate this, one could perform the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (or other applicable tests) multiple times with multiple testing correction at many (or all possible) time points, however this would be less efficient and more difficult to interpret than other measures discussed in this chapter.

7.1.2 Houwelingen’s \(\alpha\)

As opposed to evaluating distributions at one or more arbitrary time points, one could instead evaluate distribution predictions at meaningful times. van Houwelingen proposed several measures (Van Houwelingen 2000) for calibration but only one generalises to all probabilistic survival models, termed here ‘Houwelingen’s \(\alpha\)’. The measure assesses if the model correctly estimates the theoretical ‘true’ cumulative hazard function of the underlying data generating process, \(H = \hat{H}\).

The statistic is derived by noting the closely related nature of survival analysis and counting processes. In brief, for an observation \(i\) one could define the counting process \(N_i(\tau) = \mathbb{I}(T_i \leq \tau, \Delta_i = 1)\), which represents the number of events \(i\) has experienced at \(\tau\). Clearly in single-event survival analysis this will be \(0\) before the event has been experienced or \(1\) at or after the event. An important quantity in counting process is the ‘intensity process’, which is the instantaneous rate at which events occur given past information. This is related to, but distinct from the hazard rate. The core difference is that the intensity process incorporates real-world information via the individual risk indicator, \(R_i(\tau) = \mathbb{I}(T_i \geq \tau)\). Hence the hazard and intensity are related via \(\lambda_i(\tau) = R_i(\tau) h(\tau|\mathbf{x}_i)\). The intensity process can itself be thought of as the expected number of events at \(t\), which is \(0\) if the event has already occurred at \(R_i(\tau) = 0\) or equal to \(h(\tau|\mathbf{x}_i)\) otherwise (Hosmer Jr, Lemeshow, and May 2011). Therefore the expected number of events between \([0, \tau]\) can be obtained by the cumulative intensity process

\[ \Lambda_i(\tau) = \int^\tau_0 \lambda_i(s) \ ds = \int^\tau_0 R_i(s) \ h(s|\mathbf{x}_i) \ ds = \int_0^{\min\{\tau, t_i\}} h(s|\mathbf{x}_i) \ ds = H(\min\{\tau, t_i\}, \mathbf{x}_i) \tag{7.1}\]

A particularly useful quantity is the expected number of events for individual \(i\) in \([0, t_i]\), which can be seen from (7.1) reduces to \(H(t_i|\mathbf{x}_i)\). In a perfect model one would expect \(\hat{H}(t_i|\mathbf{x}_i) = 1\) if \(\delta_i = 1\) and \(0\) otherwise. Hence summing over all observations, \(\sum \hat{H}(t_i|\mathbf{x}_i)\) gives the total number of expected events in the dataset. Houwelingen’s \(\alpha\) exploits this result to provide a simple method for assessing calibration by comparing the actual and expected number of events:

\[ H_\alpha(\boldsymbol{\delta}, \hat{\mathbf{H}}, \mathbf{t}) = \frac{\sum_i \delta_i}{\sum_i \hat{H}(t_i|\mathbf{x}_i)} \]

with standard error \(SE(H_\alpha) = \exp(1/\sqrt{\sum_i \delta_i})\) (Van Houwelingen 2000). A slightly more useful metric is given by \(H_\alpha(\boldsymbol{\delta}, \hat{\mathbf{H}}, \mathbf{t}) - 1\) which is lower-bounded at \(0\) and can therefore be minimized in automated tuning processes. A model is then well-calibrated if \(H_\alpha = 0\).

The next metrics we look at evaluate models across a spectrum of points to assess calibration over time.

7.2 Probabilistic Calibration

Calibration over a range of time points may be assessed quantitatively or qualitatively, with graphical methods often favoured. Graphical methods compare the average predicted distribution to the expected distribution, which can be estimated with the Kaplan-Meier curve, discussed next.

7.2.1 Kaplan-Meier Comparison

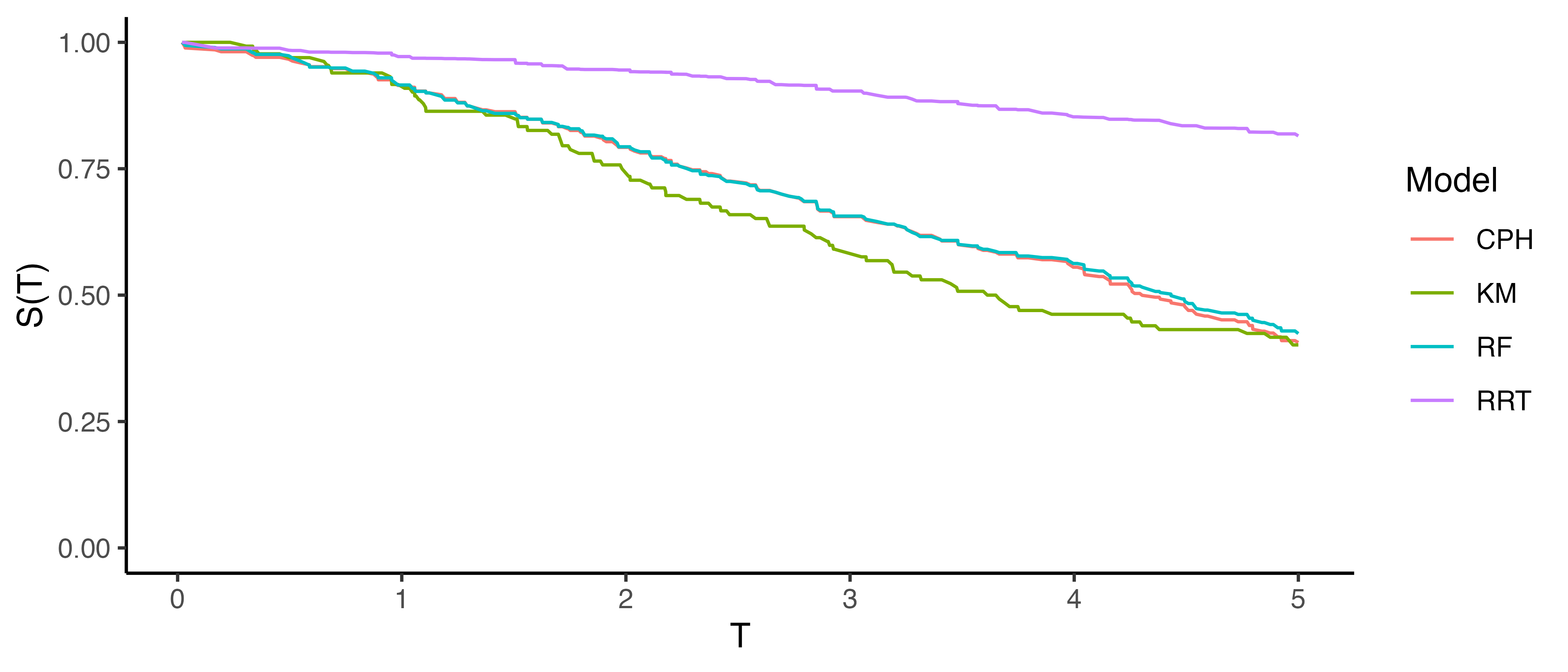

The simplest graphical comparison compares the average predicted survival curve to the Kaplan-Meier curve estimated on the testing data. Let \(\hat{S}_1,...,\hat{S}_n\) be predicted survival functions, then the average predicted survival function is the mixture: \(\bar{\hat{S}} = \frac{1}{n} \sum^{n}_{i = 1} \hat{S}_i(\tau)\). This estimate can be plotted next to the Kaplan-Meier estimate of the survival distribution in a test dataset (i.e., the true data for model evaluation), allowing for visual comparison of how closely these curves align. An example is given in Figure 7.1, a Cox model (CPH), random survival forest, and relative risk tree, are all compared to the Kaplan-Meier estimator. This figure highlights the advantages and disadvantages of this method. The relative risk tree is clearly poorly calibrated as it increasingly diverges from the Kaplan-Meier. In contrast, the Cox model and random forest cannot be directly compared to one another, as both models frequently overlap with each other and the Kaplan-Meier estimator. Hence it is possible to say that the Cox and forests models are better calibrated than the risk tree, however it is not possible to say which of those two is better calibrated and whether their distance from the Kaplan-Meier is significant or not at a given time (when not clearly overlapping).

This method is useful for making broad statements such as “model X is clearly better calibrated than model Y” or “model X appears to make average predictions close to the Kaplan-Meier estimate”, but that is the limit in terms of useful conclusions. One could refine this method for more fine-grained information by instead using predictions to create ‘risk groups’ that can be plotted against a stratified Kaplan-Meier (Austin, Harrell Jr, and Klaveren 2020), however this method is harder to interpret and adds even more subjectivity around how many risk groups to create and how to create them (Royston and Altman 2013; Austin, Harrell Jr, and Klaveren 2020). The next measure we consider includes a graphical method as well as a quantitative interpretation.

7.2.2 D-Calibration

Recall that calibration measures assess whether model predictions align with population-level outcomes. In probabilistic classification, this means testing if predicted probabilities align with observed frequencies. For example, among all instances where a model predicts a 70% probability of the event happening, approximately 70% of the corresponding observations should actually experience the event. In survival analysis, calibration is extended by examining if predicted survival probabilities align with the actual distribution of event times. This is motivated by a well-known result: for any continuous random variable \(X\), it holds that \(S_X(X) \sim \mathcal{U}(0,1)\) (Angus 1994). This means that, regardless of whether the true outcome times, \(T\), follow a Weibull, Gompertz, or any other continuous distribution, the survival probabilities evaluated at those times should be uniformly distributed in a well-calibrated model, \(\hat{S}_i(T) \sim \mathcal{U}(0,1)\).

D-Calibration (Andres et al. 2018; Haider et al. 2020) leverages the fact that the event times, \(t_i\), are i.i.d. randomly sampled event times from a distribution \(T\), which justifies replacing \(T\) with \(t_i\) (Lemma B.2 Haider et al. 2020) and so a survival model is considered well-calibrated if the predicted survival probabilities at observed event times follow a standard Uniform distribution: \(\hat{S}_i(t_i) \sim \mathcal{U}(0,1)\).

The \(\chi^2\) test-statistic is used to test if random variables follow a particular distribution:

\[ \chi^2 := \sum_{g=1}^G \frac{(o_g - e_g)^2}{e_g} \]

where \(o_g, e_g\) are respectively the number of observed and expected events in groups \(g = 1,...,G\). In this case, the \(\chi^2\) statistic is testing if there is an even distribution of predicted survival probabilities across the \([0,1]\) range. In practice the test is simplified to instead compare if \(\hat{S}_i(t_i) \sim \textrm{DiscreteUniform}(0,1)\). To do so the \([0,1]\) range is cut into \(G\) equal width bins. Now let \(n\) be the total number of observations, then, under the null hypothesis, the expected number of events in each bin is equal: \(e_i = n/G\).

To calculate the observed number of events in each bin, first define which observations are in each bin. The observations in the \(g\)th bin are defined by the set:

\[ \mathcal{B}_g := \{i = 1,\ldots,n : \lceil \hat{S}_i(t_i) \times G \rceil = g\} \]

where \(i = 1,\ldots,n\) are the indices of the observations, \(\hat{S}_i\) are predicted survival functions, \(t_i\) are observed outcome times, and \(\lceil \cdot \rceil\) is the ceiling function. For example, if there are \(5\) bins then the bins are \(\{[0, 0.2], (0.2, 0.4], (0.4, 0.6], (0.6, 0.8], (0.8, 1]\}\). So observation \(i\) would be in the fourth bin if \(\hat{S}_i(t_i) = 0.7\) as \(\lceil 0.7 \times 5 \rceil = \lceil 3.5 \rceil = 4\). Finally, the observed number of events is the number of observations in the corresponding set: \(o_g = |\mathcal{B}_g|\).

The D-Calibration measure, or \(\chi^2\) statistic, is then defined by:

\[ D_{\chi^2}(\hat{\mathbf{S}}, \mathbf{t}) := \frac{\sum^B_{i = 1} (o_i - \frac{n}{G})^2}{n/G} \]

where \(\hat{\mathbf{S}} = (\hat{S}_1 \ \hat{S}_2 \cdots \hat{S}_n)^\top\) and \(\mathbf{t}= (t_1 \ t_2 \cdots t_n)^\top\).

This measure has several useful properties. Firstly, one can test the null hypothesis that a model is ‘D-calibrated’ by deriving a \(p\)-value from comparison to \(\chi^2_{B-1}\). Secondly, \(D_{\chi^2}\) tends to zero as a model is increasingly well-calibrated, hence the measure can be used for model comparison. Finally, the theory lends itself to an intuitive graphical calibration method, known as reliability diagrams (Wilks 1990). A D-calibrated model implies:

\[ p = \frac{\sum_i \mathbb{I}(t_i \leq \hat{F}_i^{-1}(p))}{n} \]

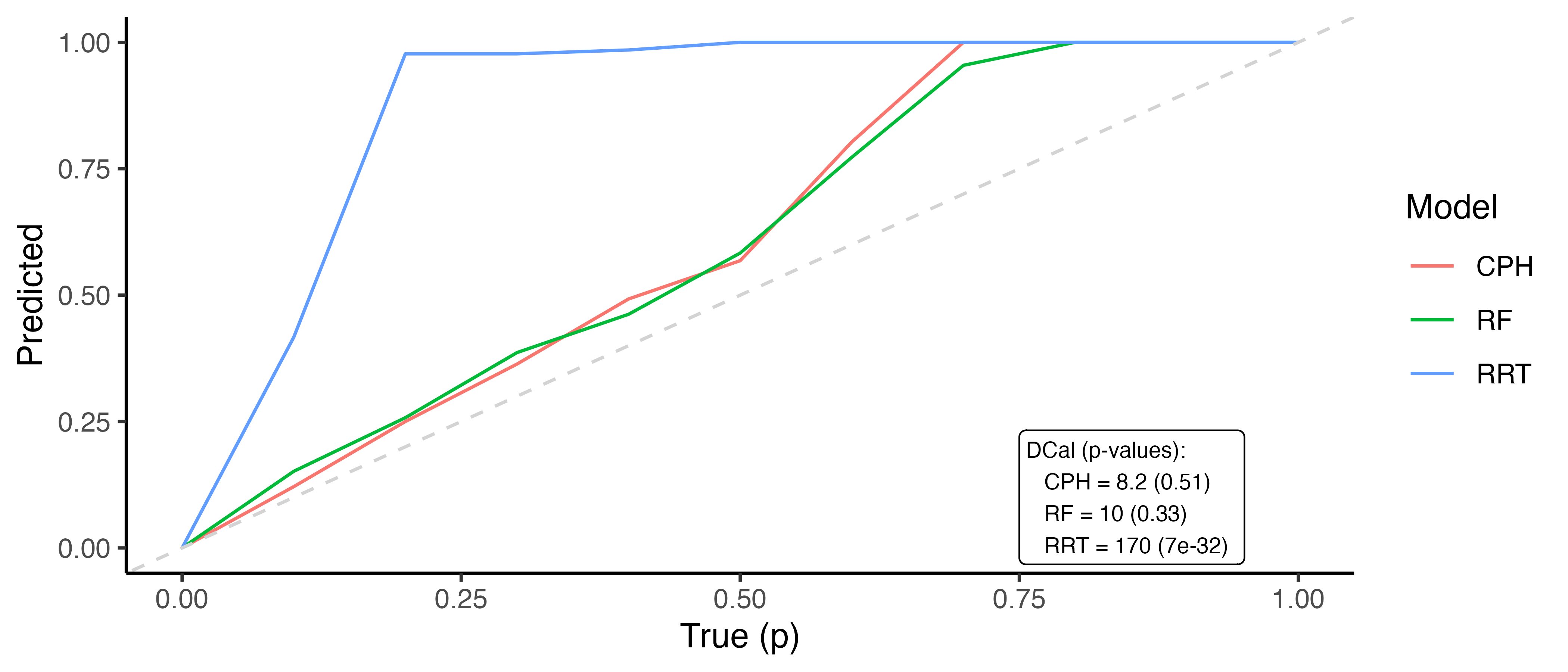

where \(p\) is some value in \([0,1]\), \(\hat{F}_i^{-1}\) is the \(i\)th predicted inverse cumulative distribution function, and \(n\) is again the number of observations. In words, the number of events occurring at or before each quantile should be equal to the quantile itself, for example 50% of events should occur before their predicted median survival time. Therefore, one can plot \(p\) on the x-axis and the right hand side of the above equation on the y-axis. A D-calibrated model should result in a straight line on \(x = y\). This is visualized in Figure 7.2 for the same models as in Figure 7.1. This figure supports the previous findings that the relative risk tree is poorly calibrated in contrast to the Cox model and random forest but again no direct comparison between the latter models is possible.

Whilst D-calibration has the same problems as the Kaplan-Meier method with respect to visual comparison, at least in this case there are quantities to help draw more concrete solutions. For the models in Figure 7.2, it is clear that the relative risk tree is not D-calibrated with \(p<0.01\) indicating the null hypothesis of D-calibration (predicted survival probabilities follow \(\mathcal{U}(0,1)\)) can be comfortably rejected. Whilst the D-calibration for the Cox model is smaller than that of the random forest, the difference is unlikely to be significant, as is seen in the overlapping curves in the figure.

7.3 Extensions

7.3.1 Competing risks

Numerical methods have been proposed for calibration in a competing risk setting, including using pseudo-measures (Schoop, Schumacher, and Graf 2011) and overall calibration ratios (Geloven et al. 2022). However, these are complex to implement and interpret and therefore graphical methods are more often used in practice (Monterrubio-Gómez, Constantine-Cooke, and Vallejos 2024).

As there is not a single survival curve in the competing risks setting, instead one can estimate the ‘true’ CIF using the Aalen-Joahnson estimator (Section 4.2.2) and plot this against the average prediction in the same way as in Section 7.2.1.

As discussed earlier in this chapter, interpreting and using calibration measures is complex enough in the single event setting. Extending this to multiple plots, one for each event, makes interpretation even more complex. Using scoring rules to capture calibration performance in the competing risks setting is likely to be more straightforward (Section 8.5).

7.3.2 Other censoring and truncation types

Using graphical plots is simplest for measuring calibration when left-censoring, interval-censoring, and/or truncation are involved. In these contexts, predicted survival functions can be compared to the ‘true’ survival probability estimated with the Kaplan-Meier (Section 7.2.1) by using non-parametric estimators that can incorporate other censoring and truncation types as required. For example the NPMLE for interval censoring and the left-truncated risk set definition for left-truncation, see Section 3.5.2 for more.